Exodus 33:12-23 Psalm 99 1 Thessalonians 1:1-10 Matthew 22:15-22

Introduction

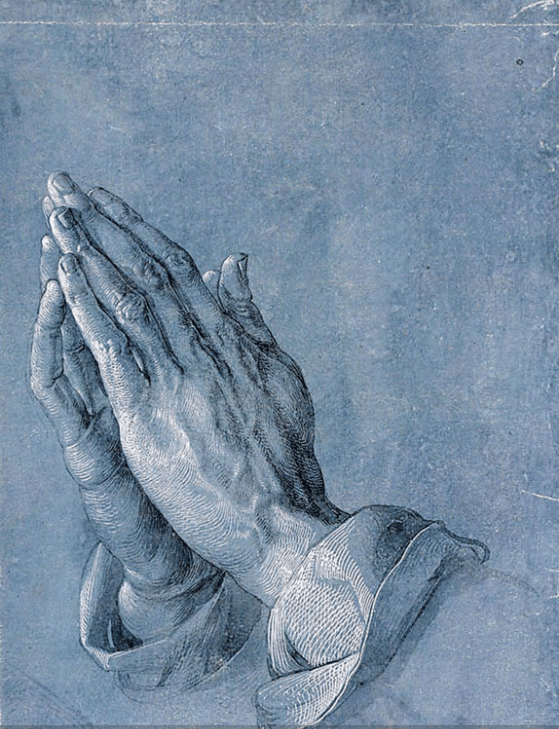

Michael Berkeley was in conversation with David Nott, consultant surgeon and Professor of Surgery at Imperial College London last Sunday on Radio 3. Here is a man who has worked tirelessly for over a quarter of a century in some of the most appalling war zones round the world. The professor mentioned turning to God in prayer at one point in this conversation. Which got me thinking: how do you pray in a situation where resources are poor, where danger is all around, and where those you treat will not share your view on life?

More importantly, how is our prayer life in the more mundane environments in which most of us live? What is prayer for, and how should we pray?

Instead of teaching theology analytically or even systematically, the book of Exodus takes the reader through a series of stories about God. In this one, Moses had been instructed by God to leave Mount Horeb taking the people with him to journey to the promised land. And Moses was not a happy-chappie.

This comes after the story of the Israelites and the Golden Calf which is legendary in hubris or arrogance of people so recently set free. And at the very moment when the people are cavorting in front of the idol constructed by their own hands, out of their own recast jewellery, God says to Moses:

Go down at once! Your people, whom you brought up out of the land of Egypt, have acted perversely (32:7).

This is a very strange directive when God refers to the Israelites – not as my chosen ones, but as your people! And it makes me smile. It is just the kind of discussion that took place in the family home in the days of my youth. When the children were behaving beautifully, it was ‘look at my wonderful children’. When the behaviour was not acceptable, it was ‘look how your children are behaving, dear’.

God continued in similar vein by saying to Moses: Go leave this place, you and the people whom you have brought up out of the land of Egypt (33:1).

And Moses quite rightly disputes with the LORD: See, you have said to me, ‘Bring up this people’; but you have not let me know whom you will send with me … Consider too that this nation is your people. (33:12f). It’s very bold disputing that can only take place between people whose relationship is secure within a family. Perhaps this is where we should aim to be in our prayer walk with God.

But just how is this theology? This story takes us to the heart of a paradox that is at the heart of the book of Exodus and indeed Scripture and one we know only too well: how is it that the creator of the whole universe chooses to enter into a relationship with finite creatures such as ourselves? This incredible encounter of request or prayer, and response reveals much about the relationship between God and Moses.

Moses to God:

Now if I have found favour in your sight, show me your ways, so that I may know you and find favour in your sight (verse 13).

Show me your ways – this has to be one of the boldest prayers in the pages of scripture, and yet it is exactly where we should be standing before God when we start to plan for the future. For we dare not set off on the journey without God’s presence going with us. It is prayed frequently in the Psalms (25:4-5, 27;11; 86:11; 143:8); and it resonates with the prayer we pray regularly for God’s will to be done on earth as in heaven. Well, it would be impossible to accomplish God’s will without discovering what it might be, wouldn’t it? So although this prayer seems incredibly audacious, it is perhaps amongst the first that we should offer to God.

God to Moses

My presence will go with you, and I will give you rest (verse 14).

I quite like the translation found in JPS (Jewish Publication Society), especially at the moment: I will go in the lead and will lighten your burden; and the comment that this should read, ‘I personally will go and will deliver you to safety’. (Deliver to a safe haven, is a common meaning of the second verb – see Deuteronomy 3:20; 25:19)

There is a deep and rich understanding of the promised land to be found in scripture, to which all kinds of persecuted groups down through the centuries have made their appeal. But for us, I suspect that the promise of divine rest has become deeply embedded in our understanding of the life to come. Alfred Lord Tennyson used the analogy of a ship making it home to a safe harbour (Crossing the Bar). Which is good; but I think perspectives at the moment are much closer to the original, when we contemplate the unknown nature of the days ahead.

Moses to God

Show me your glory, I pray. (verse 18)

Moses shows a level of audacity, by asking to see the whole of God’s very self.

At one level, this is just another unveiling of the divine which began when God first called Moses through the burning bush to lead God’s people out of slavery. At this point God reveals a name pointing to the past: ‘I am the God of your ancestors’ (Abraham, Isaac, Jacob 3:6, 15). Later on, God revealed more of the holy name at Sinai, so there is an understanding of who God is and what the Almighty has done. And it is alongside the verse in Exodus 29:46, where God wanted to dwell with the children of Israel, that makes the construction of the Golden Calf so profoundly shocking

This covenant-breaking act endangered God’s whole project of deliverance and dwelling in the midst of Israel. How can the powerful holiness and glory of the God of all creation live with and in the midst of a sinful people without the surging power of that divine holiness destroying the people (Exodus 33:3)? That is the key question with which Exodus 33:12-23 wrestles.

Dennis Olson

http://www.workingpreacher.org/preaching.aspx?commentary_id=3445

To put this into the words of the old hymn writers – while it is important to sing ‘What a friend we have in Jesus‘, there needs to be a good balance with the ‘Immortal, invisible God only wise’, in hymnody, theology and in daily life.

One of the great prayers in the Methodist tradition includes these words:

Almighty God,

to whom our needs are known before we ask,

help us to ask only what accords with your will;

and those good things which we dare not

or in our blindness cannot ask,

grant for the sake of your Son Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Moses dared to ask, and God in love and wisdom made it possible. I love this next part of the story (33:19- 23), where God puts Moses into the cleft in the rock until God has passed by. How tender is that! And Moses is permitted to view where God has just been, to catch a glimpse of the divine Presence. It is really difficult to put into words the space where God had just been, but maybe you read the Wind in the Willows as a child:

Then suddenly the Mole felt a great Awe fall upon him, an awe that turned his muscles to water, bowed his head, and rooted his feet to the ground. It was no panic terror – indeed he felt wonderfully at peace and happy – but it was an awe that smote and held him and, without seeing, he knew it could only mean that some august Presence was very, very near… and still there was utter silence in the populous bird-haunted branches around them; and still the light grew and grew.

‘Rat!’ he found breath to whisper, ‘are you afraid?’

Afraid’ murmured the Rat, his eyes shining with unutterable love. ‘Afraid of him? O never, never! And yet –and yet –O, Mole, I am afraid!’

Then the two animals, crouching to the earth, bowed their heads and did worship.

Graham Green, Chapter seven: ‘The Piper at the Gate of the Dawn’ in Wind in the Willows

http://www.writewords.org.uk/library/9030.asp [accessed 15.10.20]